(Disclaimer: As usual, I am writing here from the perspective of my personal, automotive embedded sw perspective. Below are my thoughts based on everyday-experience as an engineering manager and sw enthusiast. I am not a trained/certified test expert with deep knowledge in testing theory/science, frameworks and terminology. Please take it with a grain huge truckload of salt. Let me know your opinion!)

Introduction

After more than 17 years in automotive sw engineering, I have come to see testing as an integral part of everyday sw engineering practice. At first, such a statement seems obvious – it doesnt need 17 years to understand the importance of testing. True, but read the italic sentence again. I wrote „part of everyday […] practice“. To a suprise for some, and bitterly confirming others, this is not the case up until today in many automotice sw projects. Testing is often decoupled in various dimensions:

- Testing is done much later than the code implementation (weeks, months, years)

- Testing is executed when big SW releases are made (think: on a monthly or quarterly scale)

- Testing is done to satisfy some process requirements (again, usually late, briefly before start of production)

- Testing is done by dedicated staff in testing organizations, spacially and organizationally decoupled from the other sw roles (architects, programmers, Product Owners)

Even when talking about the lowest tier of sw testing, unit testing and coding rule compliance, much if not all of the above applies. When it comes to higher levels of testing such as integration testing or qualification testing, more and more of the above list applies.

There are many reasons why the above is bad and why it is the case. Many such issues are based on wrong mindset and corporate organizational dynamics (e.g. the infamous „make testers a shared resource decoupled from dev teams“). Those are causes I dont want to write about today. I have done so in the past and may do in the future. My focus today is on the technical meta aspects of getting testing into the right spot.

My observation is that automotive sw testing is still in a severe lack of alignment/harmonization of the test environments. While there are many sophisticated tools serving specific purposes, the overall landscape is fragmented. Many expensive, powerful domain-specific tools are combined with home-grown tooling, resulting in test ecosystems which work all by themselves, and not leveraged for cross-domain or cross-project synergies.. Now, everyone always strives to harmonize and standardize solutions, but seldom it works out. There are a lot of organizational inertia and technical challenges, so just demanding or proclaiming a standardization often does not happen at all, or if it does, it leads to situations like my all-time favorite xkcd refers to:

However, that doesn’t mean we should die before the battle. We should be clever about our approach, and balance effort vs. (potential) value. And as we know the test ecosystem is complex, we need to make up our mind where to invest. Just throwing money and hours at „testing“ will not make anything better.

A Mental Model of Testing Aspects

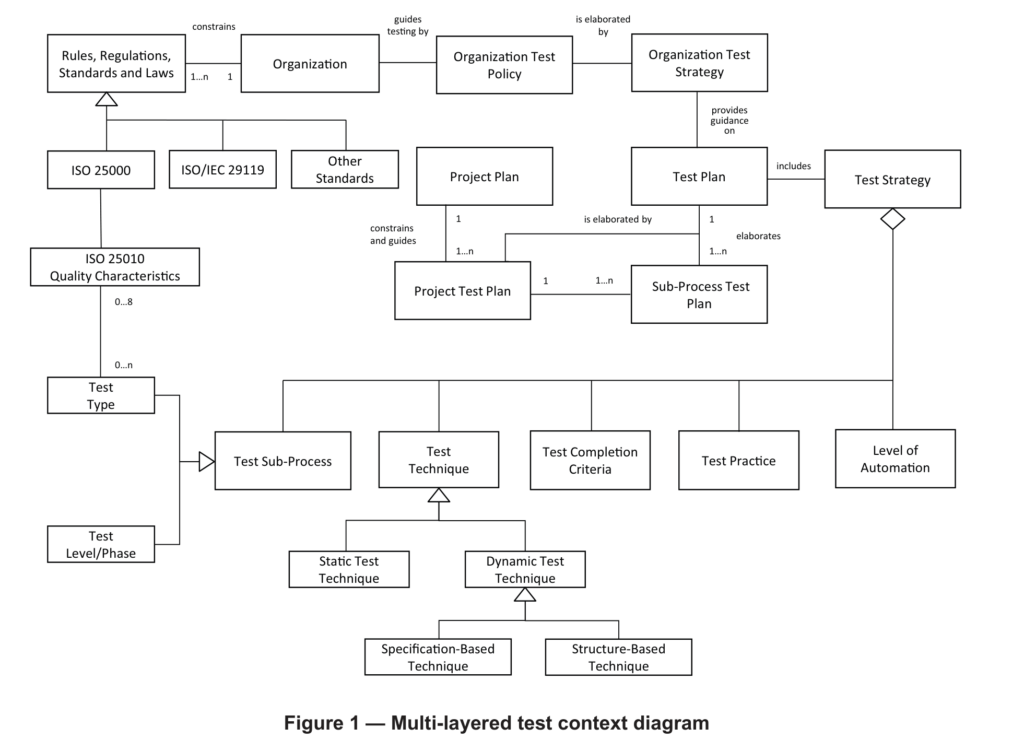

In order to see where harmonization gives the biggest bang for the buck, first we need to understand how modern testing is actually cut into pieces. I did some research and was pretty surprised that there isn’t any good model or taxonomy of testing yet described. Probably I just couldn’t find it. What one can find many times are categorizations of test types, like found here. The ISO/IEC/IEEE 29119-1 software testing standards also doesn’t really provide such a model. There is a „multi-layered test context diagram“, but it falls short in the areas where I think alignment can happen the best.

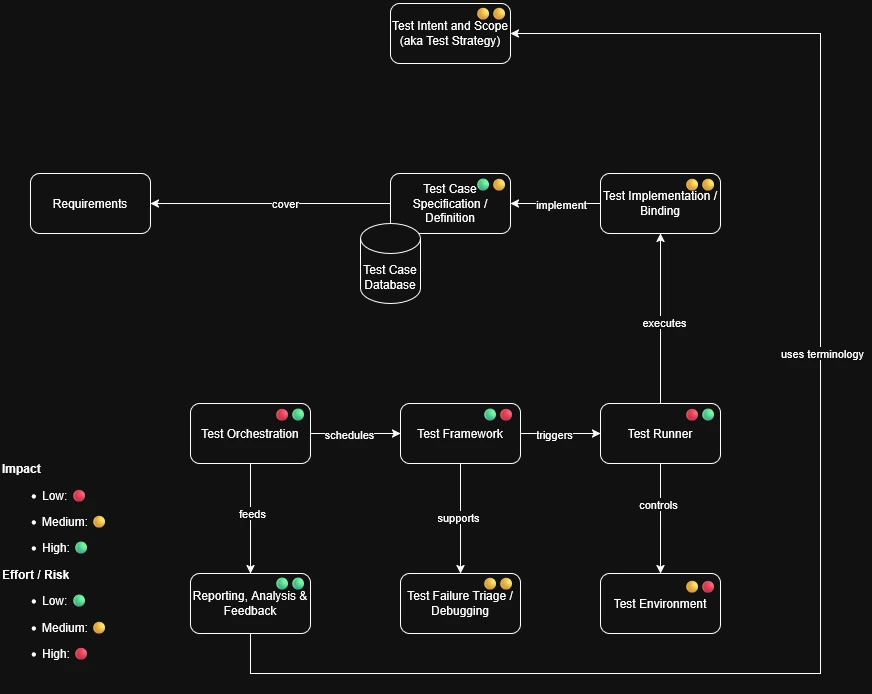

So without further ado, lets dive into my personal mental meta testing model, going from top to bottom or from outside in. And what opportunities to align and harmonize do each offer.

1. Test Intent and Scope (aka Test Strategy)

Scope: The test strategy serves to define which quality attributes are being validated by testing in a project. It can go from the classics functional correctness, interface behavior (integration testing), regression avoidance, performance to reliability, security, safety, compliance, usability, compatibility, and so on. An obvious demand by ASPICE and the like, a test strategy is often at the core of each process audit.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: Having contributed to test strategies written from (almost) scratch multiple times and seeing all the blood, sweat and tears flowing into it and, especially, refining and establishing it, I think the greatest opportunity here is to provide templates and knowledge:

- A common template gives the responsibles a skeleton which allows them to fill in the needed parts, and all „empty“ sections are a checklist.

- Besides a template, some example test strategies which passed audits are extremely helpful. If you are like me, you often wonder in which depth one shall go for a certain aspect. Shall I write a oneliner or does it require multiple pages of text with nicely crafted graphics? Examples can help to find the sweet spot of „just enough“.

- Talking about examples, best practices are extremely valuable and a shared body of knowledge can bring a struggling organization from zero to hero. All it requires is to overcome the not-invented-here syndrom. There is so much good stuff out there, even in your org. You just gonna have to find it.

- While the test strategy can be authored with any reasonably capable text editing format (Microsoft Word, Atlassian Confluence, …), what I have come to appreciate is using lightweight markup languages like Markdown or Sphinx. They enable handling the document as code, version track it and, ideally, even maintain alongside the actual project code.

2. Test Case Specification / Definition

Scope: Defines what the test is in an abstract sense. Each test case is described in a structure, which contains preconditions, input/stimuli, and expected outputs. Here, tracability to requirements, risks, code, variants and equivalence classes are documented. Last, but operationally very relevant are the metadata for each test case, like its priority, tags, ownership, status, etc.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment:

- Test cases should be maintained in an accessible database. Like any good software culture, the test cases should be as widely shared among testers from different projects as code is shared between software developers. As above, I think such a database is ideally done via plain text formats. If this is not an option, make sure to get your tester’s and developer’s input on the proper tool choice. A bad tool choice can severely impact testing operations and cost a lot of sunk money – I can speak from experience.

- Test cases should be written with as low as possible depedency on following process steps (like test frameworks and test tooling). This makes them reusable, but also decouples them from their implementation and execution, allowing for an exchange in the tooling.

- The representation of each test case should be via structured text. Natural language can be used in comments, but only structured text can be parsed in precise manner (LLMs could change this on the long run, but not yet).

- Establish a common language. There are great options out there. From the Behavior-Driven Design culture we got Gherkin or the Robot Framework test data syntax.

3. Test Implementation / Binding

Scope: Maps abstract test case specification to executable behavior. Here it usually gets very tooling specific. Here is, where APIs are implemented and keywords are bound to code (e.g. a „connect“ from step 2 is mapped to „ssh root@192.168.0.1“). A lot of efforts are spent on test setup and teardown to prepare and cleanup.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment:

- A strong culture of reusable test implementation needs to be established here. E.g. setting up the test environment can – and often is done – via very hacky means. Using established and well-maintained patterns helps.

- Define an explicit „test contract“: For each test, or your whole test set/suite, explicit state which guarantees they can uphold:

Test X guarantees:

- deterministic result under condition Y

- idempotent execution

- no persistent state - Keep Environment Knowledge Out of Tests: Tests should not know URLs, credentials, ports, hardware topology

- Some deeper technical topics:

- Invert control of assertions and actions. Instead of hard-coding test tooling specific instructions like

assert response.status_code == 200 # pytest-specific semantics

use an abstraction to define what a positive response means:test.assert.status_ok(response) # test.assert.* is our own abstraction - Don’t import test environment specifics in your immediate test implementation, only in the adapters.

- Seperate the „What“ from the „How“ using capability interfaces.

- Make test steps declarative, not procedural. Good example:

- action: http.request

method: GET

url: /health

expect:

status: 200 - Centrealize test utilities as products, not helpers. Maintain them with semantic versioning.

- Decouple test selection from test code. Instead of

pytest tests/safety/test_error_management.py

preferrun-tests --tag safety --env TEST

This is extremely powerful, as it enables test selection in a metadata-driven fashion.

- Invert control of assertions and actions. Instead of hard-coding test tooling specific instructions like

Ultimately, accept that 100% tool independence is a myth — design for easy replaceability. The goal is not “tool-free tests”, but cheap tool replacement. Success criteria could be that tool-specific code <10–20% of total test code, switching a runner requires new adapter, not rewriting tests and new project reuses 70–90% of test logic.

4. Test Framework

Scope: The test framework provides the strcuture for test implementation. It does so by managing the test execution lifecycle, providing fixtures (a fixture sets up preconditions for a test and tears them down afterward), enables mechanisms for parameterization and provides reporting hooks. It can also manage failure semantics, like retry on fail or handling flakiness. There are many test frameworks out there, some of them somewhat locked in to a specific programming language and test level (pytest, JUnit, gtest), others are versatile and independent (Cucumber, Robot Framework).

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: In my experience, there are far too many test framework in use in multi-project organizations. Often, historical developments have led test frameworks being adopted. On top, test frameworks are often in-house developed as either existing ones are unknown or lacking needed functionality (or not-invented-here hits). The opportunity here is both obvious, yet hard to retrieve: Forcing multiple projects/sub-organizations to drop their beloved test framework in order to adopt another one defined centrally will cause a lot of frustration and lead to temporary loss of pace. On the other hand, strategically, it makes total sense to nourish an iterative harmonization. If you want to go for this path, I recommend to chose either an open source solution or a home-grown solution managed in an inner source fashion. While there may be attractive and powerful proprietary solutions on the market, by experience such will always have a harder time for long-term adoption. Topics like license cost, license management, improvements will always be a toll, causing friction and making dev teams seek for other solutions, again.

Adding some highly personal opinion, any test framework which wants to prevail on the long-term has to have at least following properties:

- Run on Linux

- Run in headless fashion (no clunky GUI)

- Fully automatable

- Configuration as code

- No individual license per seat (so either license free, or global, company-wide license)

The above properties are not meant to be exclusive, if a tool also supports Windows and has an optional GUI, thats ok. But there is no future in that, and it actively hinders adoption.

5. Test Runner

Scope: Executes tests in a concrete process. A test runner can resolve the execution order (e.g. if test Y depends on test X), parallelize tests on one test target (if possible), manage timeouts, isolates processes and collects the test results. Runners are often stateless executors.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: Test frameworks often (always?) bring their test runners with them. The same observation from the Test Framework section applies here: instead of tightly coupling runners to frameworks, consider decoupled runners using containerization.

6. Test Environment

Scope: Defines where the tests run. While the test runner is typically just a tool which executes instructions on a test environment, the test environment itself defines the test execution environment: Which product targets (ECU variant X, Hardware revision Y, …), Simulators, cloud vs. on-premise, network topology, test doubles (mocks, stubs). Important aspects to cover here are provisioning (how is test software deployed = flashed?), which configuration needs to be applied to get to a running test environment, lifecycle management.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: Managing test environments can be very domain-specific. Often its done by documentary means, like big Excel tables containing variant information about a ECU test fleet in the lab. Applying infrastructure as code solutions like Ansible can help to create reproducible, scalable and reliable test environments. Going one step further, one may adopt managed test fleets like AWS Test Farm or use solutions like OpenDUT.

7. Test Orchestration

Scope: Coordinates what runs, when, and where. I think test orchestration is an underestimated portion of the whole. Often people don’t even realize its existence. In its simplest form, a nightly cronjob or jenkins pipeline which runs executes some tests is a test orchestration. However, a pretty unsophisticated one. Test orchestration in a more capable form can:

- Manually/automatically select tests (by tags, risk, code change, failure history)

- Distribute execution to multiple test runners/targets

- Handle dependencies (above individual test case scale, see test runner)

- Schedule test execution

- Automatically quarantine test runners/targets (e.g. in case of failure)

Test orchestration is a central coordination layer, and therefore, extremely important in diverse tool landscape, as it enables tool mixing.

As mentioned, often CI pipelines are used for test orchestration. Another solution is LAVA. And of course, again, your choice of in-house solution.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: I would say, a test orchestration solution is nothing which should be harmonized with priority. Its better to focus on other parts of this model for alignment efforts. Why? While test orchestration is important and extremely helpful, having same test orchestration across many projects is rather the endgame than the starting phase. Having that said, if the testing community can agree on a common test orchestration approach early on, why not.

8. Test Failure Triage / Debugging

Scope: A grayzone in the scope of testing is the handle of failures beyond merely reporting them. While I would agree, its not formally part of testing scope, it certainly requires tester contribution in a cross-functional engineering team.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: While debugging a specific bug tends to be pretty project-specific, I still see opportunities for the sharing of knowledge and best practices how exactly to combine testing with debugging efforts:

- How to make logs and traces available. I am seeing test activities which barely provide no logs about a failure (one extreme) to a plethora of logs potentially overwhelming the debugger (other extreme). Finding the right balance in between those extremes requires experience and experimentation. Cross-project best practice sharing can improve the maturity curve here.

- Accessibility of logs is very important. There is a difference if all the logs are well accessible with one link, nicely structured in an overview, or if the logs have to be pulled via 4 different storage services with different user access mechanisms.

- LLMs seem to have a lot of potential. We are still in an early phase here, and its clear that beyond trivial bugs* you cannot just throw logs at an LLM and expect it find the root cause. It will likely find a lot of potential causes, e.g. because its lacking about expected misleading log messages which were always there. Context is key, e.g. by augmenting the prompts with Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), Model Contex Protocol connections to tools (MCP) and providing a body of expert knowledge („ignore error message XY, its always there“).

- * talking about trivial bugs, every software engineer incl tester knows that a majority of bug tickets is, in fact, trivial in some sense. There are duplicates, flukes, layer 8 problems, known limitations, etc. Wading through those is a major source of frustration and conflict, and LLMs have a huge potential to help here.

9. Reporting, Analysis & Feedback

Scope: Handles what happens after execution. Here, test results are aggregated, trends are analyzed, coverage metrics are put together, failures are clustered, flakiness statistics are gathered. Here, management, process customers and project-external customers are coming in as consumers, additional to the (often neglected) internal engineering workforce. While former layers detect failures, this one interprets them and puts them in context.

Pragmatic opportunities for cross-project alignment: The good thing is, that on this level we are clearly outside the area where project-specific tooling is required. Standardization here doesn’t (or does barely) constrain testing tooling. Hence, this is one lowest risk, highest return-on-investment layer for alignment.

Obviously, the way the reports are aggregated can be aligned in a cross-project manner. Dashboards which show cross-project data yet are possible to be filtered down to each project’s or sub-project’s slice can be very instructive for (project) management.

If we exclude Defect Management but focus on actual test results, a precondition is to have aligned terminology, taxonomy and understanding of testing across projects, closing the loop to section Test Intent and Scope (aka Test Strategy).

Naturally, the focus of consumers will be on failed test cases more than passed ones. A unified failure taxonomy can contribute to align, too: Whether it is a product defect, a test tool defect (not relevant for customers), data defect, environment defect, flakiness, timing/performance degradation can make a huge difference.

It helps to agree on definitions, not thresholds first: What is a pass rate, how are process time intervals like „mean time to detect“, „mean time to repair“ defined, how are flakiness rates determined and coverages calculated.

Closing words

I have been pondering about this topic for many months, and I am glad I finally have put all my thoughts in words and a graphic:

I am looking forward to feedback. I am sure my evaluations are not globally agreeable, so I would be happy to enter a constructive discussion.