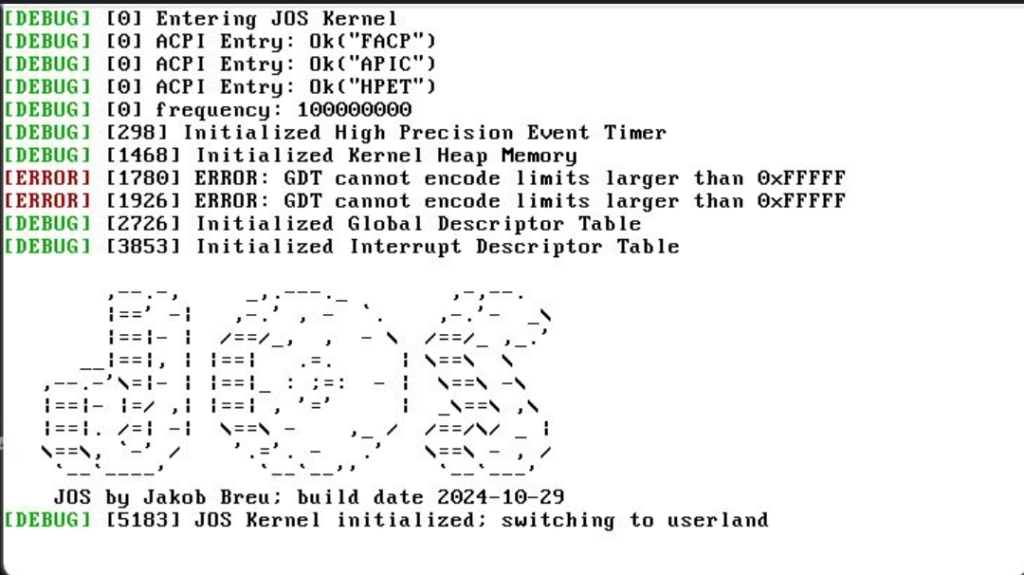

When I published my work around my own operating system JOS many moths back, my former colleague and friend Alexander suggest that in order to make my OS useful, it requires bash. Little did he (or me) know, but this lead to a one year long endeavour to get a shell working.

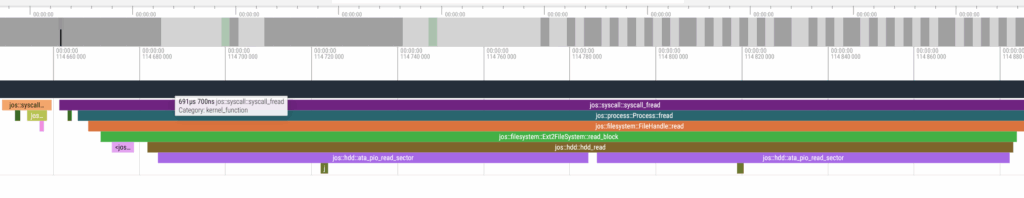

One bug enabler was the implementation of filesystem and disk drivers, I wrote already about it. When that was ready I started to get the source code of the bash (Bourne Again Shell), the most widely used shell. However, it turned out that porting it to another OS is pretty complex. So halfway through, I switched to dash (Debian Almquist Shell), reading somewhere on this internet that its portability is better. Less known by its name, its the default shell in Ubuntu. So I reckoned that going for it will give me a sufficiently powerful shell for long-term use.

So, how do you get a shell running on a written-from-scratch operating system? Like any other userspace program, you need to get its dependencies straight – which is you get all its mandatory standard library headers and implementations in, including additional system calls the kernel did not yet implement.

So first step was to compile (not yet link) all the dash source code against my own libc headers. This already took me long time, to get all the function declarations in place for the compile to go through. The result was pretty scary, sooo many functions with complex POSIX functionality I would have to implement! A lot of stuff I didn’t even hear about before, yet understand its inner workings.

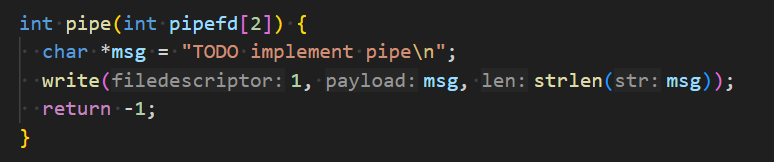

When I went on to the linking phase, I had to provide those implementations. As I saw no way to get all of them right and implemented them in a fully correct manner, I chose to basically implement them all first in a no-op version, returning error by default:

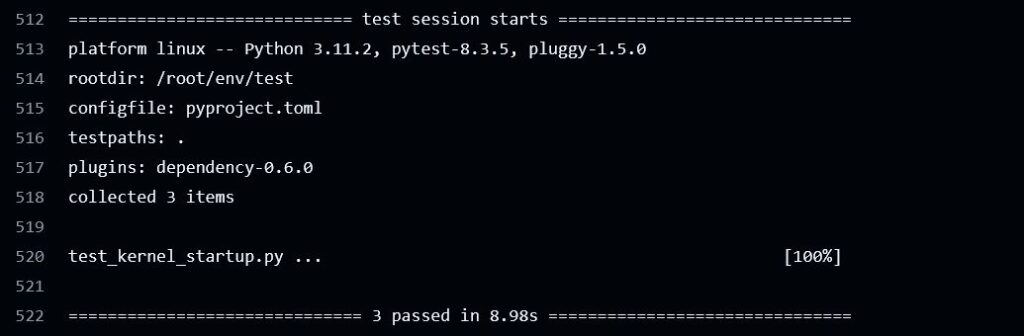

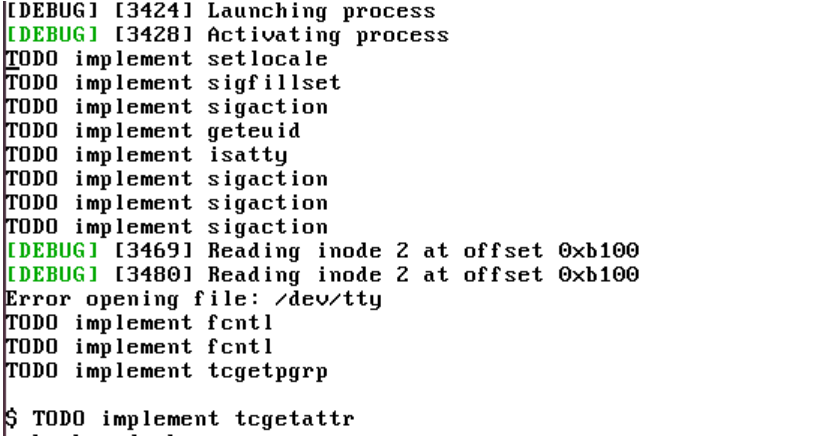

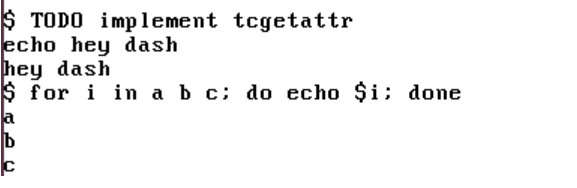

This allowed my dash to actually compile and link and procude a dash executable. Now I could get to the juicy stuff. Of course, I couldn’t just expect all the no-op failing functions lead to a running shell. Some functions were really required to function. This phase required a lot of trial-and-error. Having reached the first $ symbol (the marker for user input), you can see that till now, many functions are not implemented, but obviously are not required for minimal functionality.

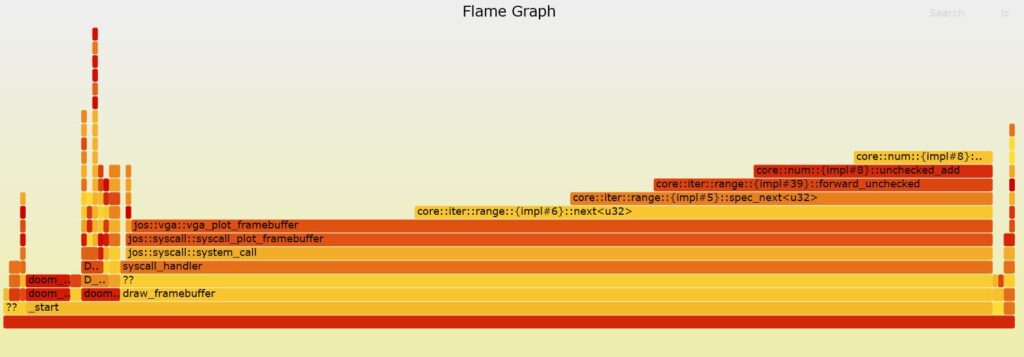

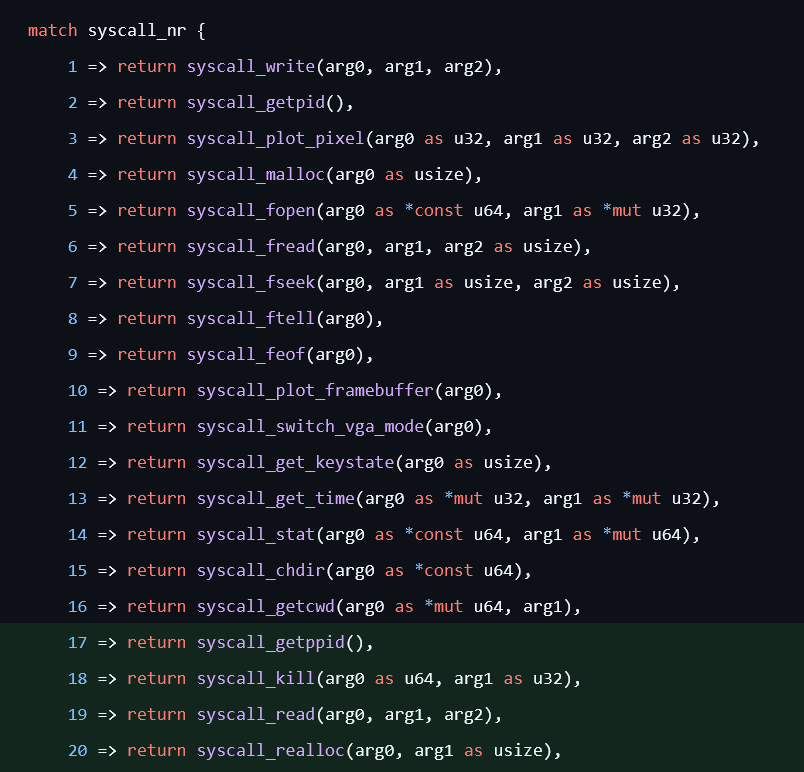

Some libc functionality could be covered on userspace side, with some workarounds. E.g. many printf variants like vsnprintf can be implemented with sprintf under the hood. Others required some additional kernel functionality. You can see in the next screenshot the syscalls I had to add (actually kill isnt used).

So finally, around christmas I was able to actually run some first shell commands, like echo or simple loops, and dash would evaluate:

Compared to running Doom, this output seems pretty underwhelming, but for me its a great milestone.

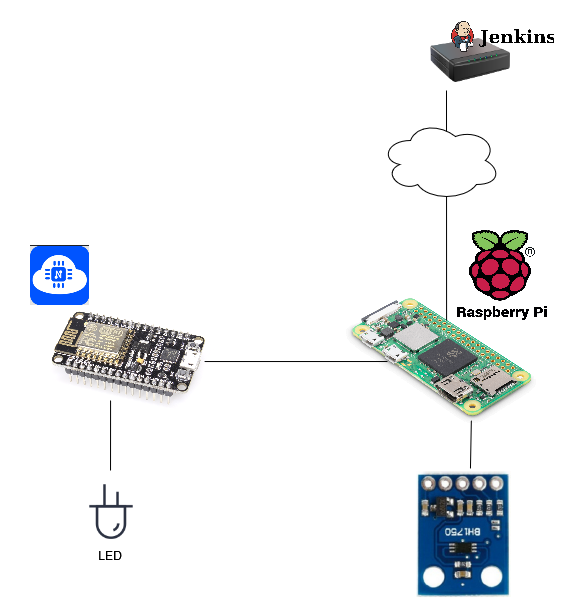

The above comes without saying, that this shell is not yet very useful. While basics are working, it is not yet capable of launching other userspace processes. I started to implement vfork and execve for this purpose and while I had some good traction in the beginning, it turned out that my kernel’s whole memory management and paging logic is just too convoluted and brittle. Hence, I set my next goal to refactor this code in order. Let’s see if and when that happens.

In case you are interested, you can find the code here: https://github.com/jbreu/jos/pull/34