I had „The Phoenix Project“ on my bookshelf for long time. As it was mentioned in our christmas townhall, this finally triggered me to read it. And man was it a read. In contrast to most other book on IT I have read before, its a novel, and it is written in a very dense way. After few tens of pages, I recommended it to my wife, leading her to devour it even faster than me. I strongly recommend this read to anyone in the IT/SW field, as its showing so many daily messy anti-patterns and ways to finally relieve them in an emotional way. Even for people for whom the teached concepts like DevOps, Lean, etc. are well-known, this book is a strong recommend.

In this article I want to collect stuff which are highlights to me. I do not attempt to provide a comprehensive summary of the plot nor the concept presented. Others have done so much better, just google for a review. But then again, better to read the book yourself and go through the rollercoaster yourself.

Disclaimer: I actually own the 5th anniversary edition of the book, which at the end also contains excerpts from „The DevOps Handbook“. Some citations below are actually from that part.

Change Management

Change Management is one of the re-occuring topics in the book.

To my surprise, Patty looks dejected. “Look, I’ve tried this before. I’ll tell you what will happen. The Change Advisory Board, or CAB, will get together once or twice. And within a couple of weeks, people will stop attending, saying they’re too busy. Or they’ll just make the changes without waiting for authorization because of deadline pressures. Either way, it’ll fizzle out within a month.”

page 44

This brings my experience with attempts to establish a pragmatic, yet effective change management. My experience is that the easier a Change Management process is established, the less it actually is proactive. Means, documenting changes already done is happening better, than managing changes before work on them actually starts. Good change managers are hard to find, who really want maintain holistic perspective on a change from business, financial to technical aspects and who can stand their ground to upper management who always (!) will want to sidestep any Change Management.

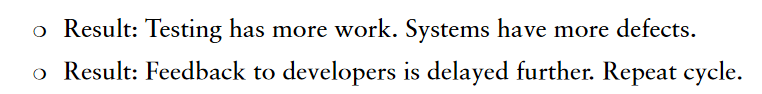

Lack of cross-functional collaboration

I’ve seen this movie before. The plot is simple: First, you take an urgent date-driven project, where the shipment date cannot be delayed because of external commitments made to […] customers. Then you add a bunch of developers who use up all the time in the schedule, leaving no time for testing or operations deployment. And because no one is willing to slip the deployment date, everyone after Development has to take outrageous and unacceptable shortcuts to hit the date.

page 53

I also have seen this movie before. In an organization with decoupled engineering teams, there is always a blame game between those who come earlier in the chain than those who come later. A typical scene:

Chris replies hotly, “Don’t give me that bullshit about ‘throwing the pig over the wall.’ We invited your people to our architecture and planning meetings, but I can count on one hand the number of times you guys actually showed up. We routinely have had to wait days or even weeks to get anything we need from you guys!”

pages 53ff, 55

[…]

Wes rolls his eyes in frustration. “Yeah, it’s true that his people would invite us at the last minute. Seriously, who can clear their calendar on less than a day’s notice?”

[…]

I nod unhappily. This type of all-hands effort is just another part of life in IT, but it makes me angry when we need to make some heroic, diving catch because of someone else’s lack of planning.

When the guys in the later process steps like testers or IT operations hint at delayed deliveries from developers leading to a crunch at their end, developers bring up that they in fact early involved them. However, that involvement is often insufficient and fragmented, if it even happens in any meaningful way.

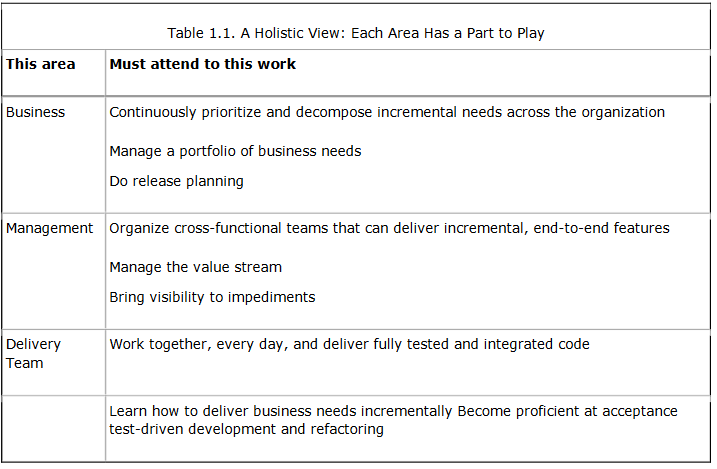

“Allspaw taught us that Dev and Ops working together, along with QA and the business, are a super-tribe that can achieve amazing things. They also knew that until code is in production, no value is actually being generated, because it’s merely WIP stuck in the system. He kept reducing the batch size, enabling fast feature flow.

page 297

Myth—DevOps Means Eliminating IT Operations, or “NoOps”: Many misinterpret DevOps as the complete elimination of the IT Operations function. However, this is rarely the case. While the nature of IT Operations work may change, it remains as important as ever. IT Operations collaborates far earlier in the software life cycle with Development, who continues to work with IT Operations long after the code has been deployed into production.

page 360 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Instead of IT Operations doing manual work that comes from work tickets, it enables developer productivity through APIs and self-serviced platforms that create environments, test and deploy code, monitor and display production telemetry, and so forth. By doing this, IT Operations become more like Development (as do QA and Infosec), engaged in product development, where the product is the platform that developers use to safely, quickly, and securely test, deploy, and run their IT services in production.

Simultaneously, QA, IT Operations, and Infosec are always working on ways to reduce friction for the team, creating the work systems that enable developers to be more productive and get better outcomes. By adding the expertise of QA, IT Operations, and Infosec into delivery teams and automated self-service tools and platforms, teams are able to use that expertise in their daily work without being dependent on other teams.

page 355 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

This enables organizations to create a safe system of work, where small teams are able to quickly and independently develop, test, and deploy code and value quickly, safely, securely, and reliably to customers. This allows organizations to maximize developer productivity, enable organizational learning, create high employee satisfaction, and win in the marketplace.

Organizing teams in cross-functional fashion, is to this day still an evergreen. Its rarely done consequently enough, and if everything goes down the drain, task forces are formed where exactly the same is happening (bringing everyone together). See my Corporate SW Engineering Aphorisms.

As Randy Shoup, formerly a director of engineering at Google, observed, large organizations using DevOps “have thousands of developers, but their architecture and practices enable small teams to still be incredibly productive, as if they were a startup.”

page 378 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

I think this is an underestimated aspect – cutting teams in product/feature verticals will only work at scale, if your system and software architecture enable according working mode.

Bottleneck Staff

A core engineer in the book is Brent. He is the go-to expert for everyone, knowing the IT systems inside out. However, this makes him the bottleneck for almost everything, from feature deployment to outage resolution.

Wes nods, “Yep. He’s the guy we need at those meetings to tell those

page 56, page 115

goddamned developers how things work in the real world and what type of

things keep breaking in production. The irony, of course, is that he can’t tell the developers, because he’s too busy repairing the things that are already broken.”

[…]

“Probably because someone like me was screaming at him, saying that I absolutely needed his help to get my most important task done. And it’s probably true: For way too many things, Brent seems to be the only one who knows how they actually work.”

“Maybe we create a resource pool of level 3 engineers to handle the escalations[…]. The level 3s would be responsible for resolving all incidents to closure, and would be the only people who can get access to Brent—on one condition. If they want to talk with Brent, they must first get Wes’ or my approval,” I say. “They’d be responsible for documenting what they learned, and Brent would never be allowed to work on the same problem twice. I’d review each of the issues weekly, and if I find out that Brent worked a problem twice, there will be hell to pay. For both the level 3s and Brent. […] Based on Wes’ story, we shouldn’t even let Brent touch the keyboard. He’s allowed to tell people what to type and shoulder-surf, but under no condition will we allow him to do something that we can’t document afterward. Is that clear?”

page 116

“That’s great,” Patty says. “At the end of each incident, we’ll have one more article in our knowledge base of how to fix a hairy problem and a growing pool of people who can execute the fix.”

Wes says, […] confirming my worst fears. “[CEO] Steve insisted that we bring in all the engineers, including Brent. He said he wanted a ‘sense of urgency’ and ‘hands on keyboards, not people sitting on the bench.’ Obviously, we didn’t do a good enough job coordinating everyone’s efforts, and…” Wes doesn’t finish his sentence.

page 178

Patty picks up where he left off, “We don’t know for sure, but at the very least, the inventory management systems are now completely down, too. […]”

He pauses and then says emphatically, “Eliyahu M. Goldratt, who created the Theory of Constraints, showed us how any improvements made anywhere besides the bottleneck are an illusion. Astonishing, but true! Any improvement made after the bottleneck is useless, because it will always remain starved, waiting for work from the bottleneck. And any improvements made before the bottleneck merely results in more inventory piling up at the bottleneck.”

page 90

I’ve also come across otherwise smart guys who are of the mistaken belief that if they hold on to a task, something only they know how to do, it’ll ensure job security. These people are knowledge Hoarders.

David Lutz, https://dlutzy.wordpress.com/2013/05/03/the-phoenix-project/

As a solution, Dr. Goldratt defined the “five focusing steps”:

page 401 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

– Identify the system’s constraint.

– Decide how to exploit the system’s constraint.

– Subordinate everything else to the above decisions.

– Elevate the system’s constraint.

– If in the previous steps a constraint has been broken, go back to step one, but do not allow inertia to cause a system constraint.

All those money quotes highlight that a hero culture is detrimental to a mature organization. Pulling heroic actions every once in a while may seem unavoidable, but its never a sign of good management to depend on it. Use your heroes to bring kick-ass customer features in an orderly process before your competition, but dont require heroes for everyday tasks.

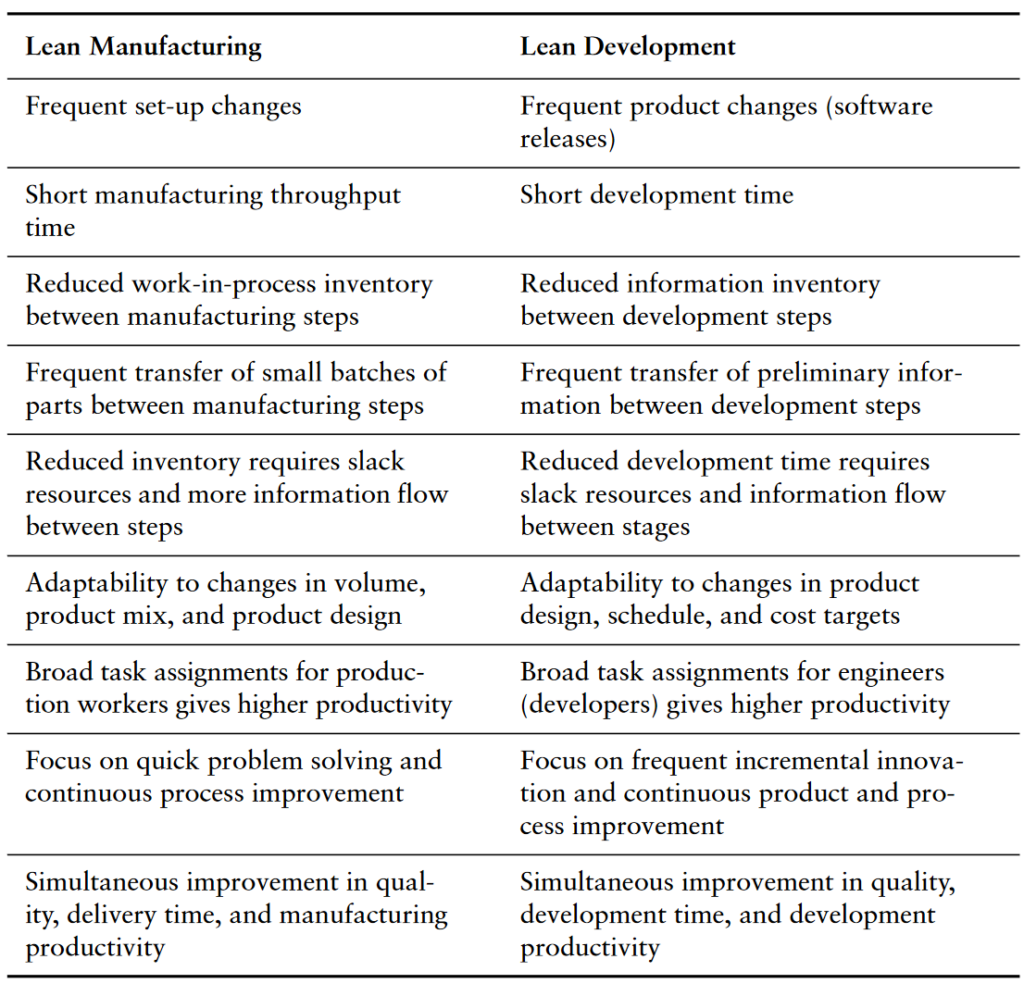

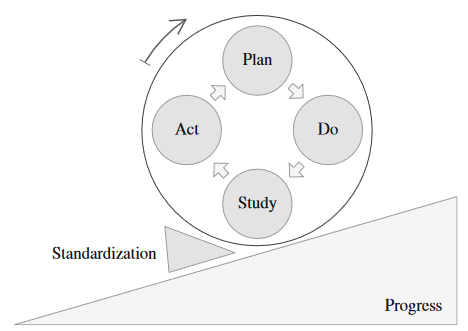

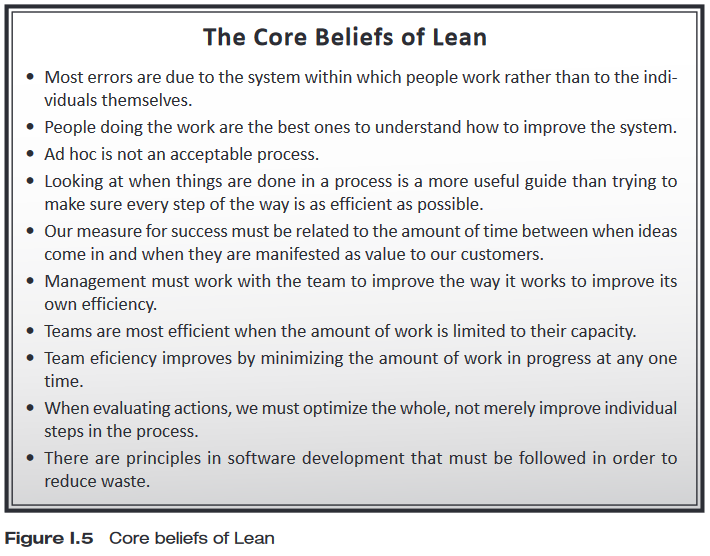

WIP is the silent killer

He gestures broadly with both arms outstretched, “In the 1980s, this plant was the beneficiary of three incredible scientifically-grounded management movements. You’ve probably heard of them: the Theory of Constraints, Lean production or the Toyota Production System, and Total Quality Management. Although each movement started in different places, they all agree on one thing: WIP is the silent killer. Therefore, one of the most critical mechanisms in the management of any plant is job and materials release. Without it, you can’t control WIP.”

page 89

Dominica DeGrandis, one of the leading experts on using kanbans in DevOps value streams, notes that “controlling queue size [WIP] is an extremely powerful management tool, as it is one of the few leading indicators of lead time—with most work items, we don’t know how long it will take until it’s actually completed.”

page 397 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Limiting Work in Progress has been one of my guiding principles for a decade. Since I am in project or line management, it has shown to be the most effective way to get a handle on any messy situation. However, its not easy at all to limit WIP. Rarely, its just about saying No often enough. More often, its about combining efforts in clever ways, breaking complex tasks down, aligning on exact requirements and expectations. But it all starts with a relentless assessment of the situation.

Stakeholder Management

Uncertain, I ask Steve, “Are we even allowed to say no? Every time I’ve asked you to prioritize or defer work on a project, you’ve bitten my head off. When everyone is conditioned to believe that no isn’t an acceptable answer, we all just became compliant order takers, blindly marching down a doomed path. I wonder if this is what happened to my predecessors, too.”

page 196

It doesn’t work without top management. If yours is continuously sidestepping any reasonably pragmatic process and ignore requests for priorization, it shows their lack of management skills, not yours (but they will make sure you feel the opposite).

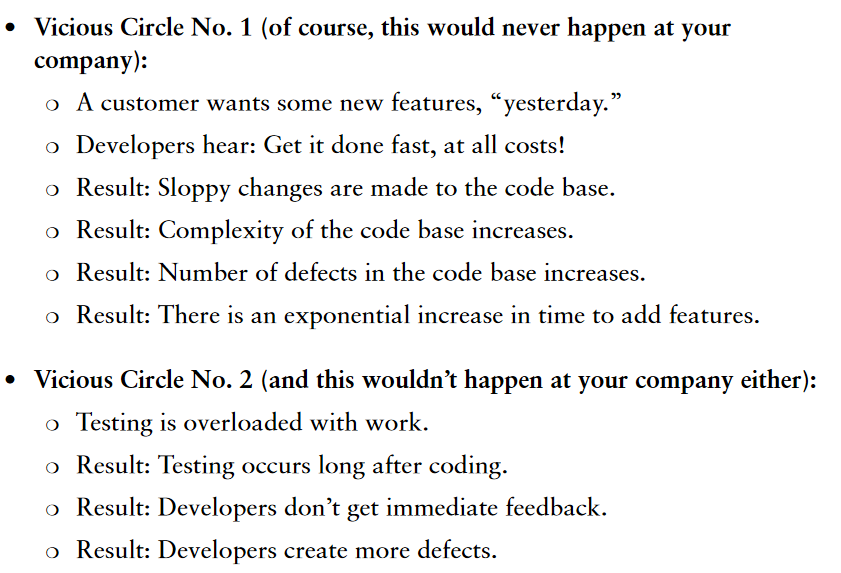

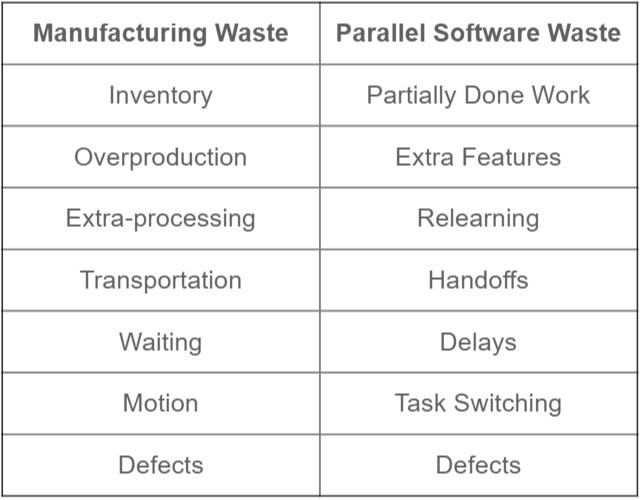

Continuous Improvement

“Mike Rother says that it almost doesn’t matter what you improve, as long as you’re improving something. Why? Because if you are not improving, entropy guarantees that you are actually getting worse, which ensures that there is no path to zero errors, zero work-related accidents, and zero loss. […] Rother calls this the Improvement Kata […] He used the word kata, because he understood that repetition creates habits, and habits are what enable mastery. Whether you’re talking about sports training, learning a musical instrument, or training in the Special Forces, nothing is more to mastery than practice and drills. Studies have shown that practicing five minutes daily is better than practicing once a week for three hours. And if you want to create a genuine culture of improvement, you must create those habits.”

page 213

Like the legendary stories of the original Apple Mac OS and Netflix cloud delivery infrastructure, we deployed code that routinely created large-scale faults, thus randomly killing processes or entire servers. Of course, the result was all hell breaking loose for an entire week as our test, and occasionally, production infrastructure crashed like a house of cards. But, over the following weeks, as Development and IT Operations worked together to make our code and infrastructure more resilient to failures, we truly had IT services that were resilient, rugged, and durable.

page 329

John [Security] loved this, and started a new project called “Evil Chaos Monkey.” Instead of generating operational faults in production, it would constantly try to exploit security holes, fuzz our applications with storms of malformed packets, try to install backdoors, gain access to confidential data, and all sorts of other nefarious attacks.

Of course, Wes tried to stop this. He insisted that we schedule penetration tests into predefined time frames. However, I convinced him this is the fastest means to institutionalize Erik’s Third Way. We need to create a culture that reinforces the value of taking risks and learning from failure and the need for repetition and practice to create mastery. I don’t want posters about quality and security. I want improvement of our daily work showing up where it needs to be: in our daily work.

John’s team developed tools that stress-tested every test and production environment with a continual barrage of attacks. And like when we first released the chaos monkey, immediately over half their time was spent fixing security holes and hardening the code. After several weeks, the developers were deservedly proud of their work, successfully fending off everything that John’s team was able to throw at them.

Because we care about quality, we even inject faults into our production environment so we can learn how our system fails in a planned manner. We conduct planned exercises to practice large-scale failures, randomly kill processes and compute servers in production, and inject network latencies and other nefarious acts to ensure we grow ever more resilient. By doing this, we enable better resilience, as well as organizational learning and improvement.

page 376 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Using chaos spreading tools like Chaos Monkey is something we are currently exploring. I dont know (nor have I researched yet) if this is done beyond typical fuzzing approaches in embedded, but I see a lot of potential here.

Throughput

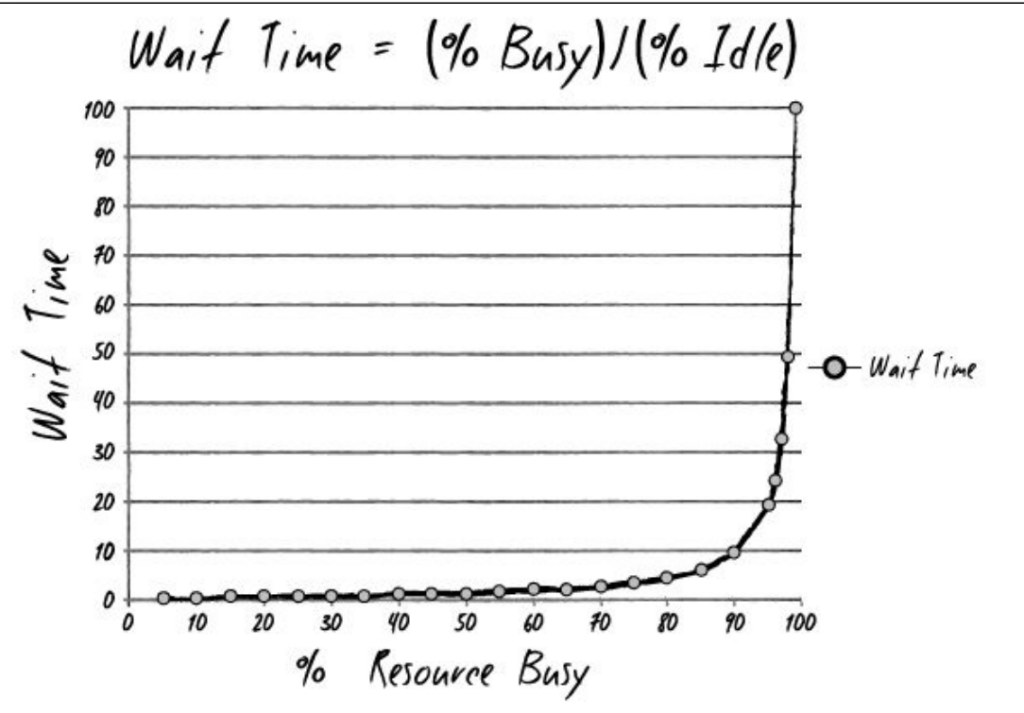

I tell them […] about how wait times depend upon resource utilization. “The wait time is the ‘percentage of time busy’ divided by the ‘percentage of time idle.’ In other words, if a resource is fifty percent busy, then it’s fifty percent idle. The wait time is fifty percent divided by fifty percent, so one unit of time. Let’s call it one hour. So, on average, our task would wait in the queue for one hour before it gets worked. “On the other hand, if a resource is ninety percent busy, the wait time is ‘ninety percent divided by ten percent’, or nine hours. In other words, our task would wait in queue nine times longer than if the resource were fifty percent idle.” I conclude, “So, for the Phoenix task, assuming we have seven handoffs, and that each of those resources is busy ninety percent of the time, the tasks would spend in queue a total of nine hours times the seven steps…”

page 235f

“What? Sixty-three hours, just in queue time?” Wes says, incredulously […]

Patty says, “What that graph says is that everyone needs idle time, or slack time. If no one has slack time, WIP gets stuck in the system. Or more specifically, stuck in queues, just waiting.”

Naturally, as the book is about lean concepts, throughput plays an important role. With the above I actually learned a new aspect. The calculation of wait time from resource utilization seems a bit counterintuitive, and I haven’t bought it fully, still. However, there is certainly a strong correlation here. Your resources – be it staff or tools – should never by occupied above a certain ratio (50%? 80%?), otherwise your full value stream will go down the drain.

Emotional and Motivational Aspects

When people are trapped in this downward spiral for years, especially those who are downstream of Development, they often feel stuck in a system that preordains failure and leaves them powerless to change the outcomes. This powerlessness is often followed by burnout, with the associated feelings of fatigue, cynicism, and even hopelessness and despair. Many psychologists assert that creating systems that cause feelings of powerlessness is one of the most damaging things we can do to fellow human beings—we deprive other people of their ability to control their own outcomes and even create a culture where people are afraid to do the right thing because of fear of punishment, failure, or jeopardizing their livelihood. This can create the conditions of learned helplessness, where people become unwilling or unable to act in a way that avoids the same problem in the future.

pages 372f (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Never underestimate the employee mood and commitment on your organization’s performance. Another thing which sounds obvious at first, but looking behind the curtains, listening to coffee room chatter and engaging with people’s honest opinions will always (!) reveal something you need to improve one – completely outside of any hard project KPIs. Listen.

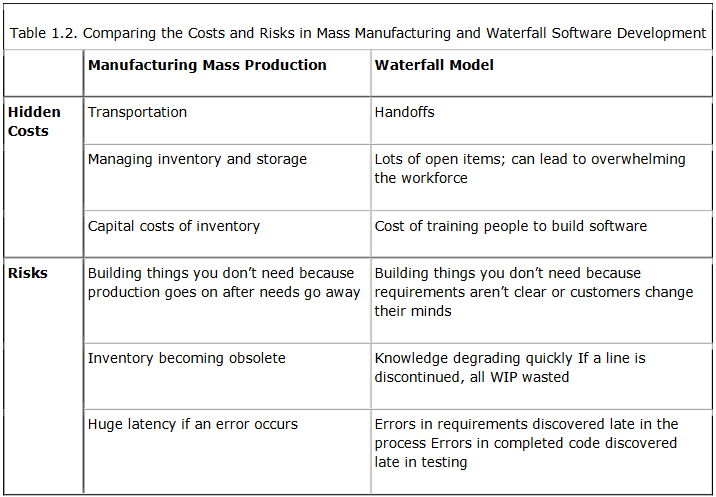

Quality and Safety

In addition to lead times and process times, the third key metric in the technology value stream is percent complete and accurate (%C/A). This metric reflects the quality of the output of each step in our value stream. Karen Martin and Mike Osterling state that “the %C/A can be obtained by asking downstream customers what percentage of the time they receive work that is ‘usable as is,’ meaning that they can do their work without having to correct the information that was provided, add missing information that should have been supplied, or clarify information that should have and could have been clearer.”

page 391 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Consider when we have an annual schedule for software releases, where an entire year’s worth of code that Development has worked on is released to production deployment. Like in manufacturing, this large batch release creates sudden, high levels of WIP and massive disruptions to all downstream work centers, resulting in poor flow and poor quality outcomes. This validates our common experience that the larger the change going into production, the more difficult the production errors are to diagnose and fix, and the longer they take to remediate.

page 399 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Dr. Sidney Dekker, who also codified some of the key elements of safety culture, observed another characteristic of complex systems: doing the same thing twice will not predictably or necessarily lead to the same result. It is this characteristic that makes static checklists and best practices, while valuable, insufficient to prevent catastrophes from occurring.

page 406 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

Examples of ineffective quality controls include:

page 411 (actually from The DevOps Handbook)

– Requiring another team to complete tedious, error-prone, and manual tasks that could be easily automated and run as needed by the team who needs the work performed

– Requiring approvals from busy people who are distant from the work, forcing them to make decisions without an adequate knowledge of the work or the potential implications, or to merely rubber stamp their approvals

– Creating large volumes of documentation of questionable detail which become obsolete shortly after they are written

– Pushing large batches of work to teams and special committees for approval and processing and then waiting for responses

Instead, we need everyone in our value stream to find and fix problems in their area of control as part of our daily work. By doing this, we push quality and safety responsibilities and decision-making to where the work is performed […]